06 July 2007, Jennifer L. Schenker , Business Week

Faced with struggling startups and a divide between research and innovation, the science of the small has yet to make it big in the EU

Anxious investors are but one of the problems plaguing nanotechnology, the cutting-edge science of manipulating materials and microscopic devices at the atomic level.

Consider the story of Oxonica, Britain's highest-profile publicly traded nanotech startup. It revealed in late April that one of its key products—a catalyst designed to cut vehicle emissions when combined with high-sulfur diesel fuel—didn't work as expected, leading to the cancellation of a big supply deal with Turkish oil retailer Petrol Ofisi.

Oxonica shares were suspended until June, but when trading began again, the price plunged nearly 75%, wiping out $80.7 million in Oxonica's market capitalization. To save face, the company noted that Petrol Ofisi had agreed to work with it on another project involving low-sulfur diesel. But the damage was done, and Oxonica's share price is still only half what it was in April.

Research Over Real World

In many ways Oxonica is emblematic of Europe's nanotechnology sector: a story of early promise, huge hype, and dashed hopes. The Continent's single market and long history of scientific excellence suggested a natural role in the development and exploitation of nanotechnology, which could revolutionize manufacturing and medicine in coming decades. Experts say the worldwide market for engineered nanotech products could hit $1.5 trillion by 2015.

Yet despite massive injections of government money, analysts say Europe is actually doing a worse job of commercializing nanotech than other regions. According to Tim Harper, a nanotechnology specialist at London, U.S. startups have focused more on real-world applications for the technology.

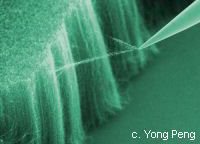

In layman's terms, that has translated into a handful of U.S. products that frankly seem almost trivial, such as stain-resistant trousers and more durable tennis balls. But the U.S. also is laying the groundwork for success in years to come by wringing out about twice as many nanotech patents as Europe has from roughly similar levels of public research funding, says Spinverse, a Finnish consultancy that advises governments and startups on nanotechnology.

The field has so far proved to be a bit of a disappointment everywhere. As of the end of 2006, governments worldwide had sunk around $24 billion of taxpayer money into nanotech research and development—roughly the same amount, in inflation-adjusted terms, spent by the U.S. on the Apollo space program. Yet eight years into Apollo, the program had already achieved its first manned flight around the moon, surely a more momentous achievement than stain-resistant slacks, quips Cientifica's Harper.

To be sure, Europe has produced some nanotech success stories. Many large companies have been looking at the science for 10 or more years and have well-developed internal programs. German chemical giant BASF (BF), for instance, has developed scratch-proof coatings made with nanoparticles. Bayer (BAY) makes nanotubes and is looking into new applications in areas such as medicines, composite materials, and surfaces. French cosmetics maker L'Oréal is using nanotechnology to make improved sunscreens, hair conditioners, and skin creams.

But Europe's nanotech startups are less successful. "They are struggling because they are not creating new markets, just competing in existing markets with larger competitors," says Rodrigo Amandi, a research analyst at Swiss financial research firm SAM Group. Europe's small caps "are not delivering something spectacular, which is what we were promised from nanotech," he says.

University/Corporate Divide

That's a concern because startups feed the innovation mill. Nanotech's real opportunity—and the real money—are yet to come, when basic building blocks are combined in new ways to deliver breakthrough products that score with the public. The trouble, analysts say, is that Europe is failing to put the right innovation pipeline in place to ensure it can cash in on the next phase.

In part that's due to the age-old schism in Europe between academia and corporate R&D. There are fewer partnerships between universities and industry than in the U.S. and Japan, and European scientists are still less inclined to leave secure research jobs at schools or corporations to start risky ventures. On top of that, European industry is investing less in nanotech than counterparts in the U.S. and Japan, European Commission figures show.

Europe's weaker entrepreneurial culture also hurts startup activity. When nanotech companies are formed in EuropeEurope gets a proportionally smaller share of global nanotechnology venture capital investment, according to Spinverse. And though public funding makes up some of the difference, it doesn't offer venture capital's other benefits, including strong industry knowledge and networking.

Shift to Health Care and Pharma

Still, says Spinverse Chief Executive Pekka Koponen, "Europe has a chance to catch up." He thinks Europe could shine in creating instruments and tools for nanotechnology. "In all gold rushes the shovel-makers were the first to make money," he says. "We could see that here also." To date, U.S. companies such as FEI (FEIC) and Veeco Instruments (VECO) are the leaders in this area, but Koponen says European contenders such as Sweden's Obducat and Russia's NT-MDT shouldn't be overlooked.

Potentially even more important is the upcoming shift from nanotech materials to applications—especially in health care and pharmaceuticals. These are fields where Europe is historically strong and already has sophisticated business networks. Cientifica's Harper notes that pharma clusters in Britain, Germany, and Switzerland could be especially successful in nourishing nanotech startups.

With such "ecosystems" in place and policy changes on the books to help nanotech move more easily from lab to marketplace, Europe still could become a global leader in nanotech. The science of the small could eventually have a very big impact. consultancy Cientifica, while European firms have emphasized research into materials such as nanotubes and nanopowders, they often lack clear business models and exit strategies, and their teams tend to be short on commercial experience. That's one reason

No comments:

Post a Comment