2 July 2007

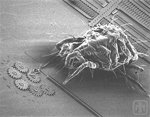

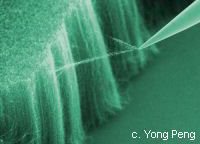

A two-millimeter square block of carbon nanotubes, made up of millions of individual, vertically aligned, multiwalled nanotubes. Credit: Rensselaer/Victor Pushparaj

The ability of carbon nanotubes to withstand repeated stress yet retain their structural and mechanical integrity is similar to the behavior of soft tissue, according to a new study from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

When paired with the strong electrical conductivity of carbon nanotubes, this ability to endure wear and tear, or fatigue, suggests the materials could be used to create structures that mimic artificial muscles or interesting electro-mechanical systems, researchers said.

The report, “Fatigue resistance of aligned carbon nanotube arrays under cyclic compression,” appears in the July issue of Nature Nanotechnology. Despite extensive research over the past decade into the mechanical properties of carbon nanotube structures, this study is the first to explore and document their fatigue behavior, said co-author Victor Pushparaj, a senior research specialist in Rensselaer’s department of materials science and engineering.

“The idea was to show how fatigue affects nanotube structures over the lifetime of a device that incorporates carbon nanotubes,” Pushparaj said. “Even when exposed to high levels of stress, the nanotubes held up extremely well. The behavior is reminiscent of the mechanics of soft tissues, such as a shoulder muscle or stomach wall, which expand and contract millions of times over a human lifetime.”

Pushparaj and his team created a free-standing, macroscopic, two-millimeter square block of carbon nanotubes, made up of millions of individual, vertically aligned, multiwalled nanotubes. The researchers then compressed the block between two steels plates in a vice-like machine.

The team repeated this process more than 500,000 times, recording precisely how much force was required to compress the nanotube block down to about 25 percent of its original height.

Even after 500,000 compressions, the nanotube block retained its original shape and mechanical properties. Similarly, the nanotube block also retained its original electrical conductance.

In the initial stages of the experiment, the force needed to compress the nanotube block decreased slightly, but soon stabilized to a constant value, said Jonghwan Suhr, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the

As the researchers continued to compress the block, the individual nanotube arrays collectively and gradually adjusted to getting squeezed, showing very little fatigue. This “shape memory,” or viscoelastic-like behavior (although the individual nanotubes are not themselves viscoelastic), is often observed in soft-tissue materials.

While more promising than polymers and other engineered materials that exhibit shape memory, carbon nanotubes by themselves do not perform well enough to be used as a synthetic biomaterial. But Pushparaj and his fellow researchers are combining carbon nanotubes with different polymers to create a material they anticipate will perform as well as soft tissue. The team is also using results from this study to develop mechanically compliant electrical probes and interconnects.

Source: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

No comments:

Post a Comment